Just in case, you call the hotline. The lady on the other end of the phone patiently explains what you should do in such a situation and which symptoms to pay attention to. She tells you how to properly wash your hands and what agents to use. She asks you to call again if you start to feel worse.

You try to remember as much as you can, but when you hang up the phone, the phone call is a bit of a blur.

Studies show that we forget between 29 and 72% of what the doctor tells us. [1] In addition, the more information we get at once, the more we forget.

And not only do we forget. There are also problems with comprehension, especially among older people.

People often can’t understand instructions, even in their native language

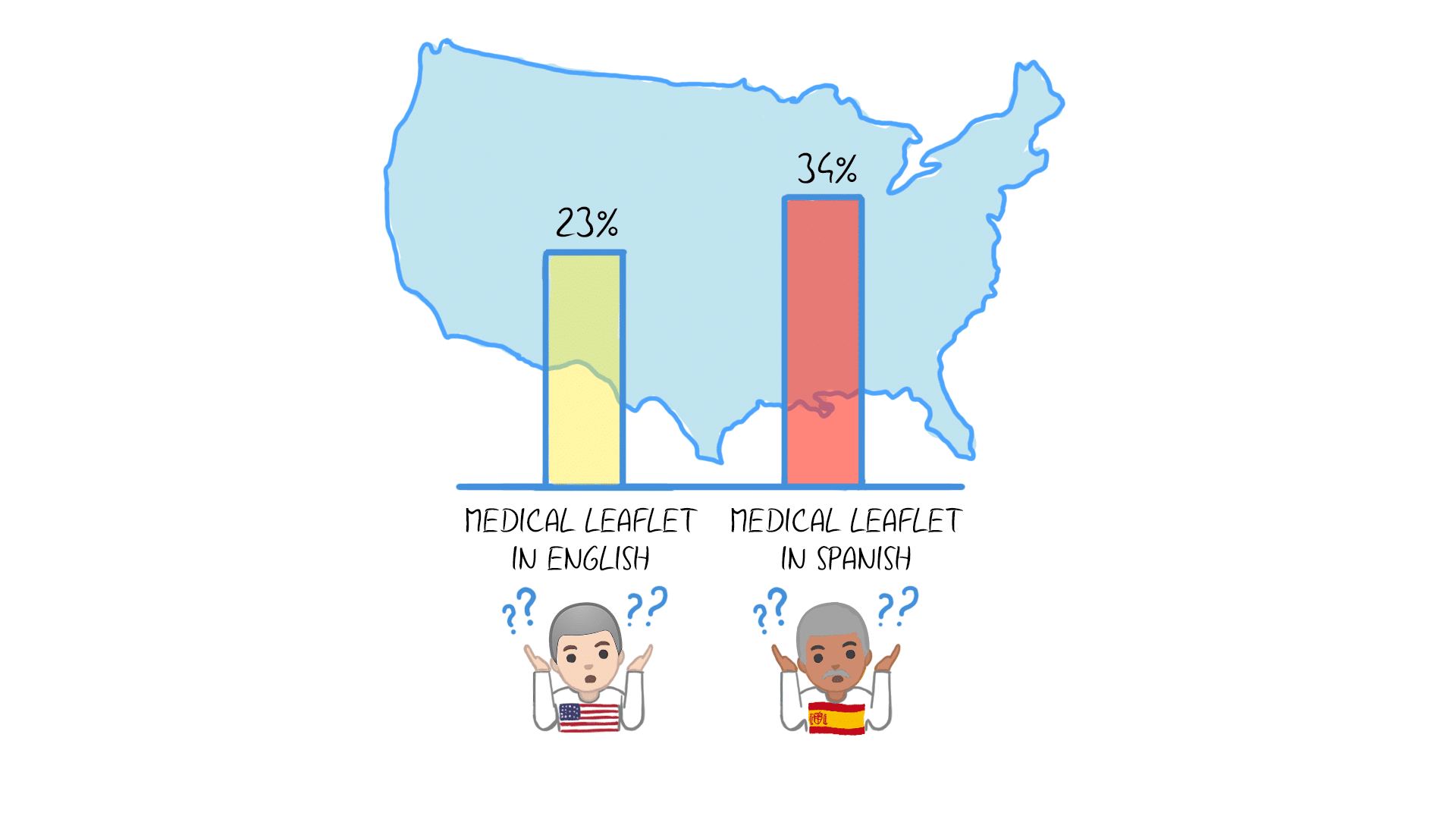

23% of English-speaking and 34% of Spanish-speaking U.S. seniors could not understand medical information in their native language. This is according to a 1999 study by Professor Julie Gazmararian of 3260 people aged 65+. [2]

English and Spanish-speaking Americans who could not understand medical information in their native language. (Gazmararian et al.)

The consequences of such a situation can be tragic – the patient’s health and life are at stake.

This applies not only to the elderly. In 2004, the Institute of Medicine released information that 48% of American adults cannot read enough to fully understand and follow medical instructions.

The release of this figure to the public was preceded by meticulous research commissioned by the Institute. It’s not that Americans can’t read at all, it’s a matter of the complexity of medical language. [3]

Doctors try to convey knowledge to patients in the simplest way possible.

Unfortunately, the language often lacks colloquial expressions for medical terms. What is obvious to a specialist, can be black magic to us! We wrote more about this topic, in a business context, in the article: The Curse of Knowledge.

What can we do to make people understand, remember and follow medical instructions?

Visual instructions reassure and educate patients

Dr. Francois Luks, a pediatric surgeon at Hasbro Hospital in the United States, appreciates the value of visuals. When he explains a diagnosis or surgical procedure to a patient, he pulls out a piece of paper and a pencil. He believes the images help patients understand complicated medical jargon.

Dr. Luks says that a boy with a serious pancreatic injury arrived at his hospital and he had to act quickly. The parents were in a panic and flooded the doctor with questions but there was no time for a long explanation. Dr. Luks took out a piece of paper, sketched the pancreas and briefly showed the stages of the operation. Then he ran into the operating theatre.

The boy came out of the surgery unscathed. The parents thanked the doctor for the drawing explaining the surgery. It made them feel less nervous during the surgery and the patient to this day keeps the doctor’s sketch as a memento. [4]

The effectiveness of images in medical communication is not only in the realm of anecdotes. It has been proven in numerous studies, collected and described by Professor Peter Houts in a review on the role of visualization in enhancing medical communication.

What kind of research?

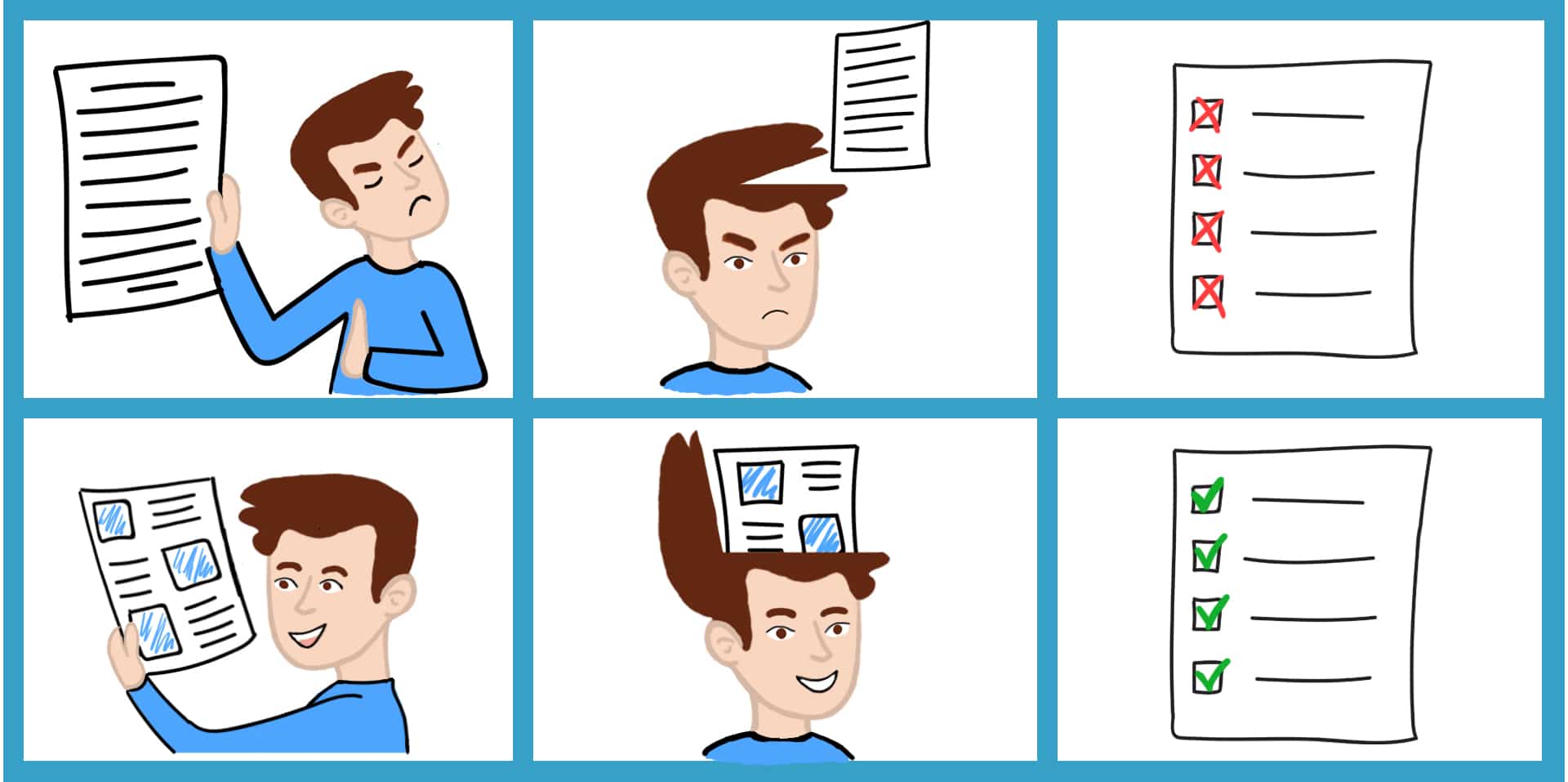

Researchers Delp and Jones conducted an experiment involving 234 people. All participants had sustained an injury and were in hospital for treatment. After being discharged, they were expected to care for the wound themselves. The healing process depended on how meticulously they cared for the wound.

They were given printed instructions in two variants. Half of the subjects got it in text form and half in text form with visualizations.

Three days later, they were asked if they had read the instructions. If they did, they were asked to answer questions and tell how they cared for the wound.

it was found that patients who received the instructions with pictures:

- were more likely to read it;

- remembered more of it;

- adhered to the instructions better.

The recommendations were followed by 77% of this group, compared to 54% of the patients who received the text-only instructions. [1]

In Delp and Jones’ experiment, patients who were given instructions with pictures were more likely to read them, remembered significantly more about the instructions and followed them better.

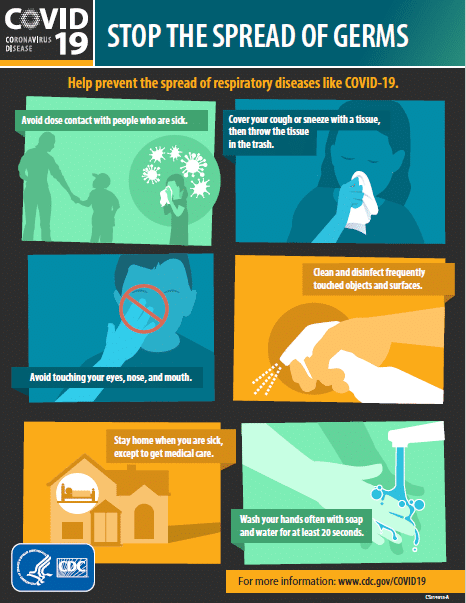

Pictorial instructions in the fight against the coronavirus outbreak

To make handwashing more effective during the ongoing coronavirus outbreak, the Ministry of Health and the State Sanitary Inspectorate, created a visual instruction. [5]

A picture-and-text graphic circulated the Polish Internet, and was displayed on housing estate staircases, in workplaces and government offices.

The same instructions in text-only form would not have had the same impact.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention infographic on preventative measures that can reduce the chances of contracting coronavirus.

Visual instructions and the memorization of information

Peter Houts came to the conclusion over 20 years ago that visual instructions could support physicians.

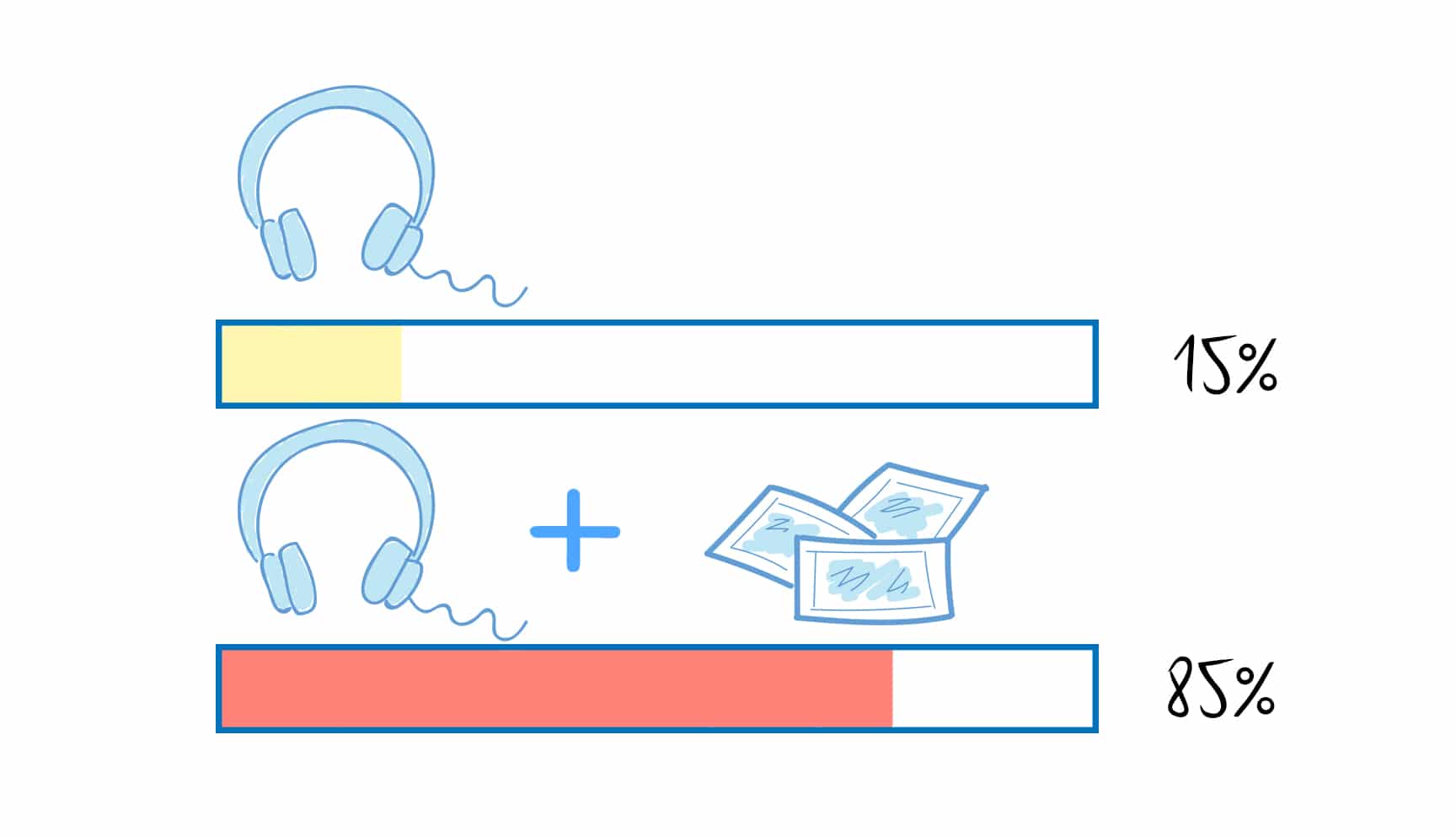

He and his colleagues conducted an experiment in 1998 involving 21 patients. They were read instructions on how to manage their disease symptoms. Each participant was subjected to the experiment twice:

- The first time, they just listened to the recording.

- The second time, the participants had supporting visualizations in front of them while listening to the instructions. They also had the visualizations in front of them while taking the test.

By having the subjects participate in both trials, the only variable was the presence of the visualizations. The outcome of the experiment strongly fell in favor of the graphics.

The respondents who listened to the text got 15% of the answers correct, while the participants in the “picture” group got as many as 85% correct. Although the study sample was small, the result was statistically significant. It has been proven that visualizations help us to understand and remember instructions better. Other studies confirm the positive impact of visualizations. [1]

In Houts’ experiment, the subjects who listened to the text got 15% of the answers correct, while the subjects in the “picture” group got as many as 85% correct.

How visualization helps you understand difficult terms

Robert Michielutte et al. gave 217 women brochures on cervical cancer prevention. [1]

This is an important topic, as in Poland women often do not go to the gynecologist for check-ups or go too late. Consequently, the survival rate is only 50%. [7]

The researchers decided to see if the form in which women get information about disease prevention makes a difference. They gave half of the women a booklet with text alone, and half with text accompanied by pictures.

Comprehension of the text was tested by asking the women eight questions. Once again, the form the information was presented was found to be important.

65% of the subjects in the group that received the illustrated booklets answered 7 or 8 questions correctly, while the same number of correct answers were given by only 53% of the women in the text group.

Importantly, the study took into account the literacy level of the women.

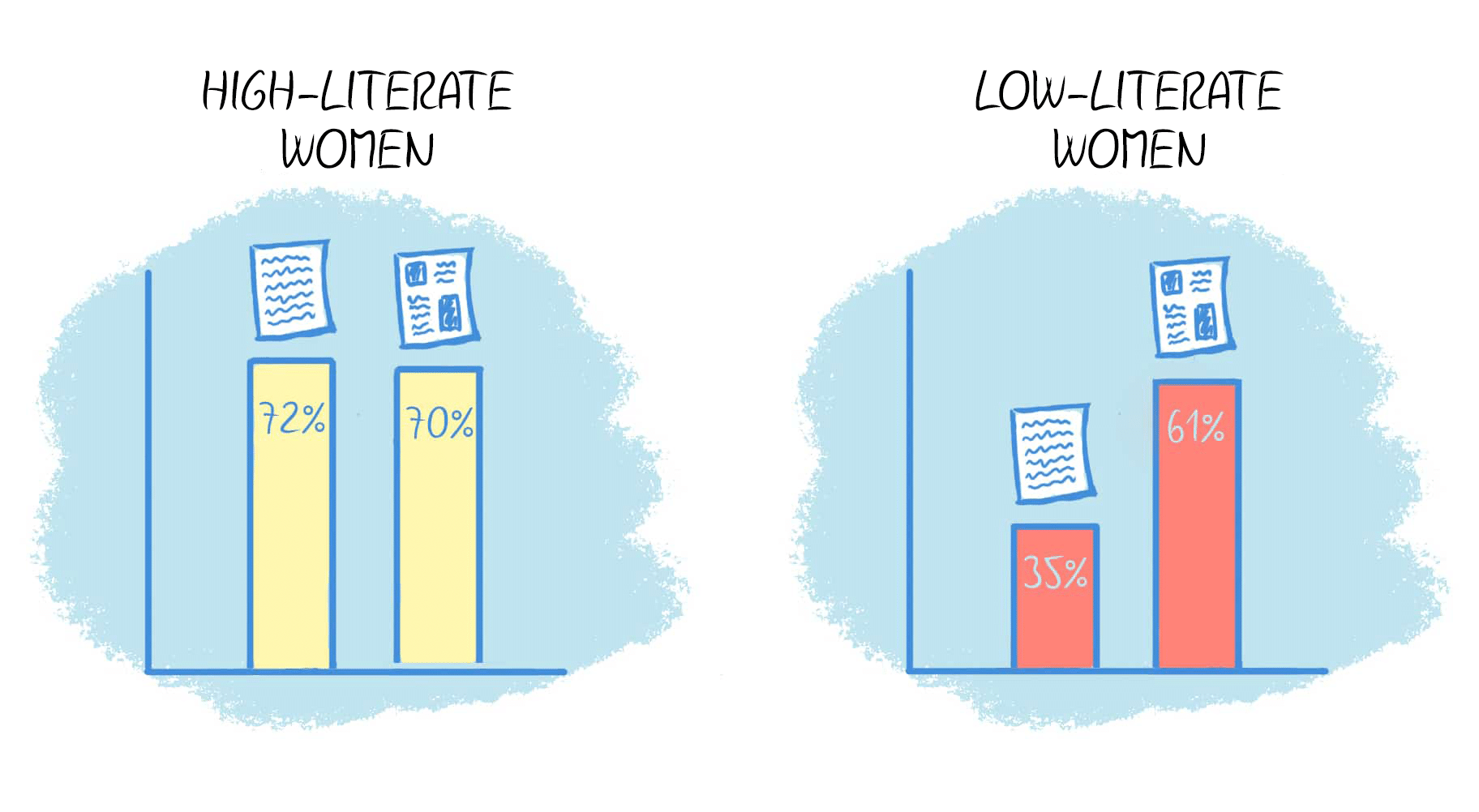

Women who were better at reading comprehension performed almost the same on the tests, regardless of the type of pamphlet they received – 7 or 8 points were scored by 72% of women who read the pamphlet without pictures, and only 2% less, or 70%, by those who received the text alone. This is a small difference and is not statistically significant.

The reverse is true for low-literate women: 7 or 8 points were given to only 35% of the women who read the booklet without pictures, and 61% of the respondents who received it with pictures. Depending on the degree of literacy, we will understand the content of the instructions better or worse. [1]

Percentage of women who read well with comprehension and less literate women who understood the instructions with pictures and with text alone in a study by Robert Michielutte et al.

When do illustrations have an advantage over photographs?

– How in words can you describe this heart without filling a whole book? Yet the more detail you write concerning it, the more you will confuse the mind of the hearer – wrote Leonardo da Vinci. [8]

The famous thinker’s advice was taken by Dr. Robert Jackler and Chris Gralapp. Dr. Jackler is a brilliant surgeon and Gralapp is an illustrator. They joined forces and with the help of pictures they explain to medical students and doctors the stages of complicated operations. They have published, among other things, an atlas of skull based surgery.

One of their readers is Dr. Richard Gurgel, who specializes in ear and skull based tumor surgery. Despite his years of experience, the day before surgery he always studies Gralapp and Jackler’s illustrations.

he says, the images are clear enough to allow me to perform the surgery in my head before I do it on a living organism.

Gralapp and Jackler’s work is so popular that its authors have made it available online. This is because sometimes surgeons would call them from the operating rooms asking for some information. Now they can easily access the book online and use it during their procedures. [9]

So it would seem that in this case, photographs would be the best solution. Meanwhile, the secret to the effectiveness of Gralapp and Jackler’s instructions lies in illustrations.

Illustrations have an advantage over pictures because they simplify what is inherently complex. Also, you can use them to show what cannot be shown with pictures because of their microscopic size.

– As an illustrator I eliminate the unnecessary – Gralapp quips. [9]

Comics also educate – both patients and doctors

Marisa Acocella Marchetto had it all – beauty, money, and love. She enjoyed life to the fullest. She loved shoes, lipstick and good wine, then one day fate turned when she discovered a tumor on her breast.

Thus began her fight with cancer, which she immortalized in her drawings. Without taboos, and with humor she showed all stages of the disease. The result of her several months’ battle is a comic book “Cancer vixen”, which helped thousands of women around the world to understand the disease. It was also appreciated by scientists and the medical profession.

It is mentioned, among others, by Professor Michael J. Green and Professor Kimberly R. Myers in an article on the role of comic books in medicine. In their opinion, both patients and doctors can benefit from pictorial stories. The former can learn more about their condition and feel that they are not alone. The latter can look at the problem from the patients’ perspective.

Moreover, in their opinion, such strong visual messages allow for an immediate understanding of complex content. This is often impossible with conventional texts.

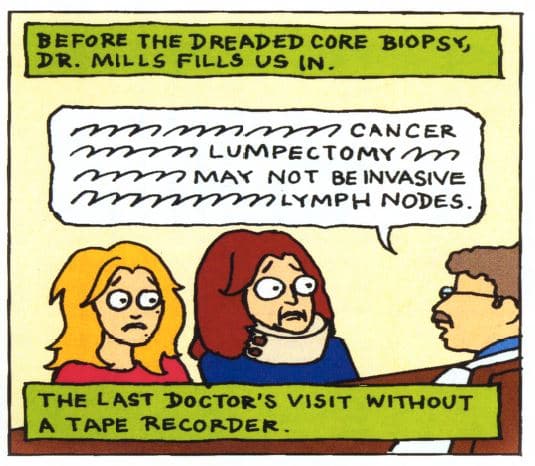

As an example, the professors cite a frame from Marchetto’s comic strip in which the author is with her mother at the doctor’s office before having a breast biopsy. The doctor is explaining the procedure. The women sit across from each other terrified.

The bubble above the doctor shows blurred lines and a few random words from the doctor – “lymph nodes”, “cancer”, “non-invasive”. You can see that the women are confused and understand very little. Thus, with just one picture, the cartoonist has exposed the problem of doctors communicating effectively with patients.

Just think of how much space and time it takes to convey this message with text compared to conveying it with one undersized frame, enthuse Professor Michael J. Green and Professor Kimberly R. Myers. [10]

The cartoons make complex medical content easier to understand while humorously demonstrating the flaws in everyday doctor-patient communication. Source: Michael J. Green, Kimberly R. Myers, Graphic medicine: use of comics in medical education and patient care in: “BMJ”, 2010

The importance of age in understanding pictorial instructions

At the beginning of this document we mentioned a study on American seniors. So does the age of the patient matter in the perception of a leaflet?

Researchers Sojourner and Wogalter decided to find out. They presented the study participants with materials in different forms: as text, images or text with images.

As with the other experiments, those who received text with visuals performed best and remembered the most information. What makes this experiment different from the others, however, is that the researchers took into account the age of the subjects.

They compared the responses of a young group (average age 19) and an older group (average age 68). The older group had overall poorer performance than the younger group, but in both groups, those who received text with pictures performed significantly better than subjects who received only text or pictures. [1]

Summary

Medical language is often difficult for patients, students, and physicians themselves to understand.

Attaching well-chosen images to texts helps people to understand it better. As studies by Houts, Delp, Michielutte and others have shown, patients are better able to understand instructions through drawings and are more likely to follow them.

This is why illustrated medication leaflets are often more effective than those containing text alone.

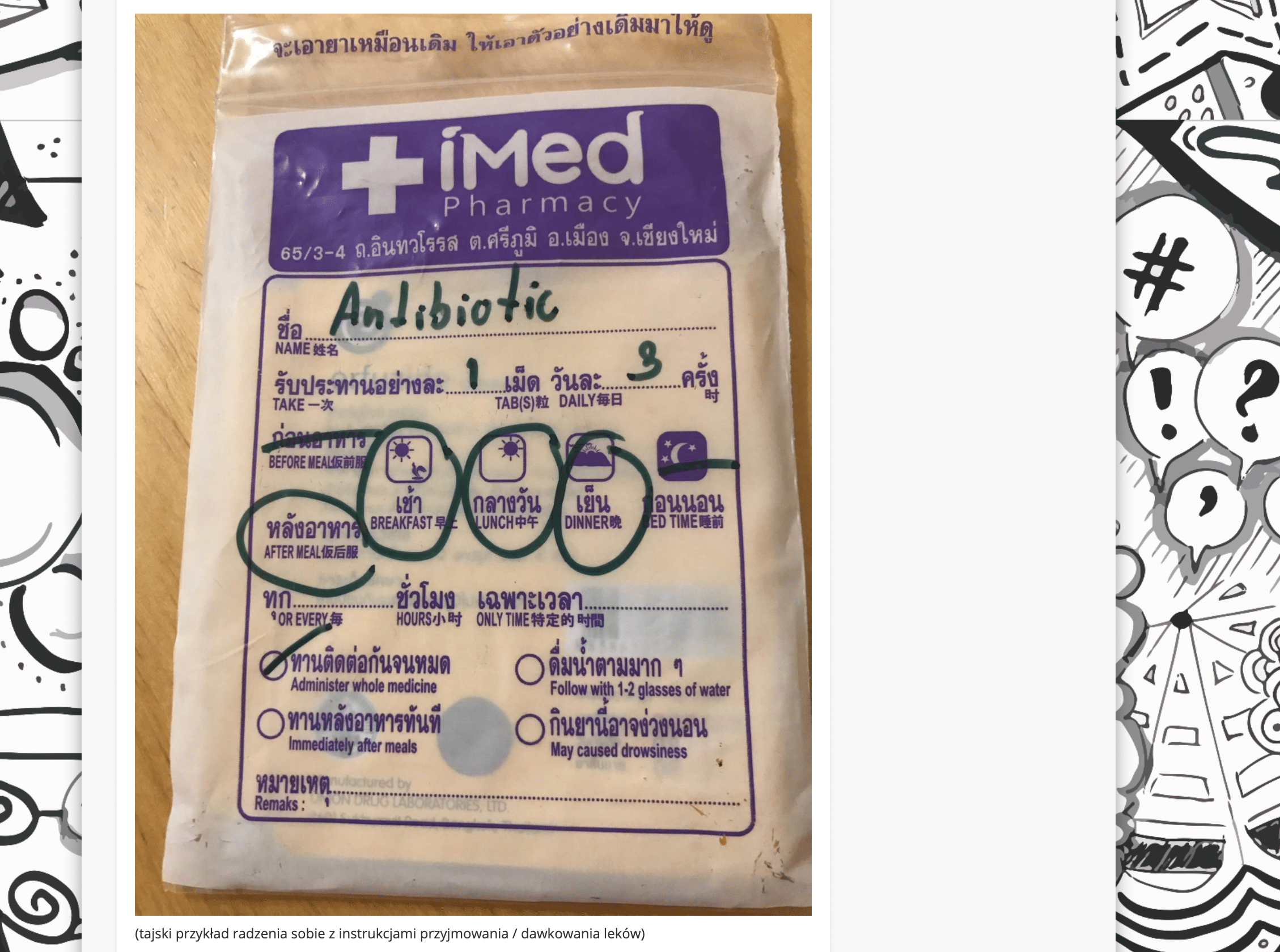

An example of a visual instruction on how to take medication, prepared by Klaudia, Creative Director of ExplainVisually our Creative Director, for her partner.

Hopefully, in the treatment of coronavirus and other ailments, doctors and patients will be supported visually. Especially since the most vulnerable are the elderly, for whom visual instruction is especially useful.

Intake/dose instructions from Thailand

Professor Peter Houts has seven recommendations:

- Health educators should look for ways to incorporate visuals into medical and health promotion communications.

Think about how you can use visuals to support the key points of your message.

- Use as simple drawings or photographs as possible.

Not every visualization is effective. So it’s important to get it right and not distract your audience with unnecessary details.

- Simplify the language.

If patients will not understand the main message, visualizations will not save the situation.

- Guide the recipient through your visualizations.

If you introduce clear captions for the illustrations, you will reduce the risk that the patient will misinterpret the visuals.

- Be culturally sensitive in your creation and selection of images.

Especially if you are communicating with people who have not had much exposure to Western medicine.

- Doctors, pharmacists, and other professionals should be actively involved in creating the visualizations.

Such collaboration will make it easier for illustrators to achieve their goals.

- Test the effectiveness of the visualization.

Most studies show that adding images positively affects attention, comprehension, memory, and adherence to instructions. However, research results have not always been consistent.

Therefore, you should test the effectiveness of this form of communication in each case, because it is possible that in some cases text alone will be more effective. Houts suggests to use the methodology described by Delp and Jones [11].

Authors: Martyna Kozłowska i Maciej Budkowski

If you want to learn more on our projects for medical idustry and how we can help you, contact us.

She studied Japanese and linguistics at the University of Warsaw, but it was her work for an NGO, first as a volunteer, and then professionally, that shaped her interests. As a coordinator of one of the campaigns she organized conferences, meetings at the Parliament, fashion shows, made interviews with politicians and celebrities. She also took care of social media and marketing. Now she is responsible for marketing and running social media at ExplainVisually.

Bibliography:

[1] Peter S. Houts, Cecilia C. Doak, Leonard G. Doak, Matthew J. Loscalzo, The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence w: „Patient Education and Counseling” nr. 61, 2006

[2] Gazmararian JA, Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Scott TL, Green DC, Fehrenbach SN, Ren J, Koplan JP,Health Literacy Among Medicare Enrollees in a Managed Care Organization, JAMA, nr. 281, 1999

[3] Institute of Medicine, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004

[4] The Importance of Medical Illustration in Patient Communication: https://in-training.org/importance-medical-illustration-patient-communication-15851

[5] Jak myć ręce? Instrukcja mycia rąk: https://gis.gov.pl/zdrowie/zasady-prawidlowego-mycia-rak/

[6] Stop the spread of germs: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/stop-the-spread-of-germs.pdf

[7] Rak szyjki macicy rozwija się długo – profilaktyka jest łatwo dostępna: http://kurier.pap.pl/profilaktyka/rak-szyjki-macicy-rozwija-sie-dlugo-profilaktyka-jest-latwo-dostepna

[8] Antony Merlin Josea, Anatomy and Leonardo da Vinci w: YALE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE 74 (2001), pp. 185-195

[9] Illustrations convey body’s secrets: https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2011/08/illustrations-convey-bodys-secrets.html

[10] Michael J. Green, Kimberly R. Myers, Graphic medicine: Use of comics in medical education and patient care w: „BMJ”, 2010

[11] Delp C, Jones J. Communicating information to patients: the use of cartoon illustrations to improve comprehension of instructions. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:264–70.