Today, we are unveiling for you the secrets of truly effective visual communication. Should you rely on illustration, or perhaps animation, to convey your message? Discover what scientific research reveals about the power of storytelling through imagery. In this exploration, we’ll tackle the essential debate of illustration vs animation to guide your strategic choices.

Walt Disney said: “Animation can represent anything the human mind can imagine. This ability makes it the most versatile and direct form of communication. At the same time, it is created to be appreciated by mass audiences.”[1]

Although this quote comes from one of the most famous creators of cartoons, there is not a shred of fiction in it. Why are animations so effective and how can they be used in business? Science provides the answer. Research clearly shows that the right combination of image and text allows people to understand and remember more.

However, it turns out that an even better effect can be achieved by using animation. Not always, of course. How best to instruct someone when printing a file, or when disassembling a machine gun? When, during a presentation on health and safety rules in a company, should animation be used, and when should illustrations? We will answer these questions below.Grasping these distinctions empowers you to choose wisely in the ongoing conversation of illustration vs animation.

Illustration and animation – the basics unveiled

Let us begin by stating that, at their core, both illustration and animation are pillars of visual art, and there can be no doubt about that. Each of these forms of visual communication possesses its own undeniable value and significance. However, if you delve deeper into the subject, you will quickly notice that they serve distinct purposes.

Illustration focuses on creating static images-often detailed works of art-that capture a single moment, concept, or idea. These static visualisations are widely used on:

- book covers,

- in editorial content,

- advertising agencies,

- publishing houses.

They allow artists to communicate ideas with clarity and emotional resonance.

On the other hand, animation breathes life into still images, introducing movement and the element of time. Through animation techniques, artists are able to create engaging content that unfolds as a story, enabling the communication of complex ideas and processes step by step.

Each of these forms requires a strong understanding of design principles, colour theory, and artistic skill.

Animation and illustration today

In the digital age, both animation and illustration have evolved significantly. Digital illustration and animation software such as adobe photoshop and adobe illustrator have become essential tools for aspiring artists and graphic designers. The creative process today often combines traditional techniques, like figure drawing, with cutting-edge technology to produce stunning visuals for a variety of applications, from advertising to feature films.

An example?

This is a technique in which illustrations are created before the viewer’s eyes – lines are drawn in real time, characters are sketched, and further elements are coloured in, while a narrator tells the story in the background or captions appear on screen.

How is furniture produced? Whiteboard animation for FORTE

Whiteboard animation harnesses both the power of static images and the dynamism of movement. It creates engaging and creative content that effectively communicates even highly complex information. What’s more, digital whiteboard animation allows for quick edits, accurate brand colour reproduction, and wide application across various digital platforms, from social media to business presentations. It is the perfect demonstration of the combination of illustration and animation.

Illustration vs animation techniques – a brief comparison

Before we move on to a detailed discussion, let us make a brief comparison.

Illustration focuses on capturing the essence of a subject in a single image, often using fine lines and a deep understanding of visual elements to communicate ideas effectively. Nowadays, graphic designers and illustrators use both traditional and digital tools to create visually appealing content, naturally leaning towards digital illustration.

Animation, on the other hand, requires a combination of artistic and technical skills. The creative process is complex and involves scriptwriting, character design, and the use of industry-standard software to produce animated content.

Traditional hand-drawn animation remains a respected art form, but the truth is that most of today’s animation industry relies on computer-generated imagery and animation software.

For those pursuing animation or a career in graphic design, the choice between these disciplines often depends on desired career outcomes and personal strengths.

Read also: Creating engaging video with hand drawn animation: A how-to guide.

1. Animations teach more effectively than illustrations

This topic was considered by two researchers, Tim N. Höffler and Detlev Leutner. In 2007, they went through 26 studies comparing understanding and remembering information conveyed through images and animations and created a meta-analysis.

They wanted to see if animations were more effective than static images. This is important because millions of people learn new things every day. When you explain new procedures to employees, you want them to understand it.

This sparked the curiosity of Tim N. Höffler and Detlev Leutner. They faced quite a challenge. No scientists before them had ever conducted such a study before. It was a huge undertaking that required careful and time-consuming statistical analysis.

The results confirmed their hypothesis – animations performed better than static images.

In 27.5% of the cases, the researchers showed a statistically significant advantage for animation, and only in 2.5% of the cases did they show a significant advantage for the image.

In the remaining comparisons, the difference was less pronounced, but still the videos performed better than the images in 71% of the cases.[2]

Although animation is more time-consuming to produce than illustrations, research shows that it is more effective at communicating and explaining complex procedures and instructions, such as health and safety.

So if 710 of 1,000 employees will understand your message it is worth considering using animation.

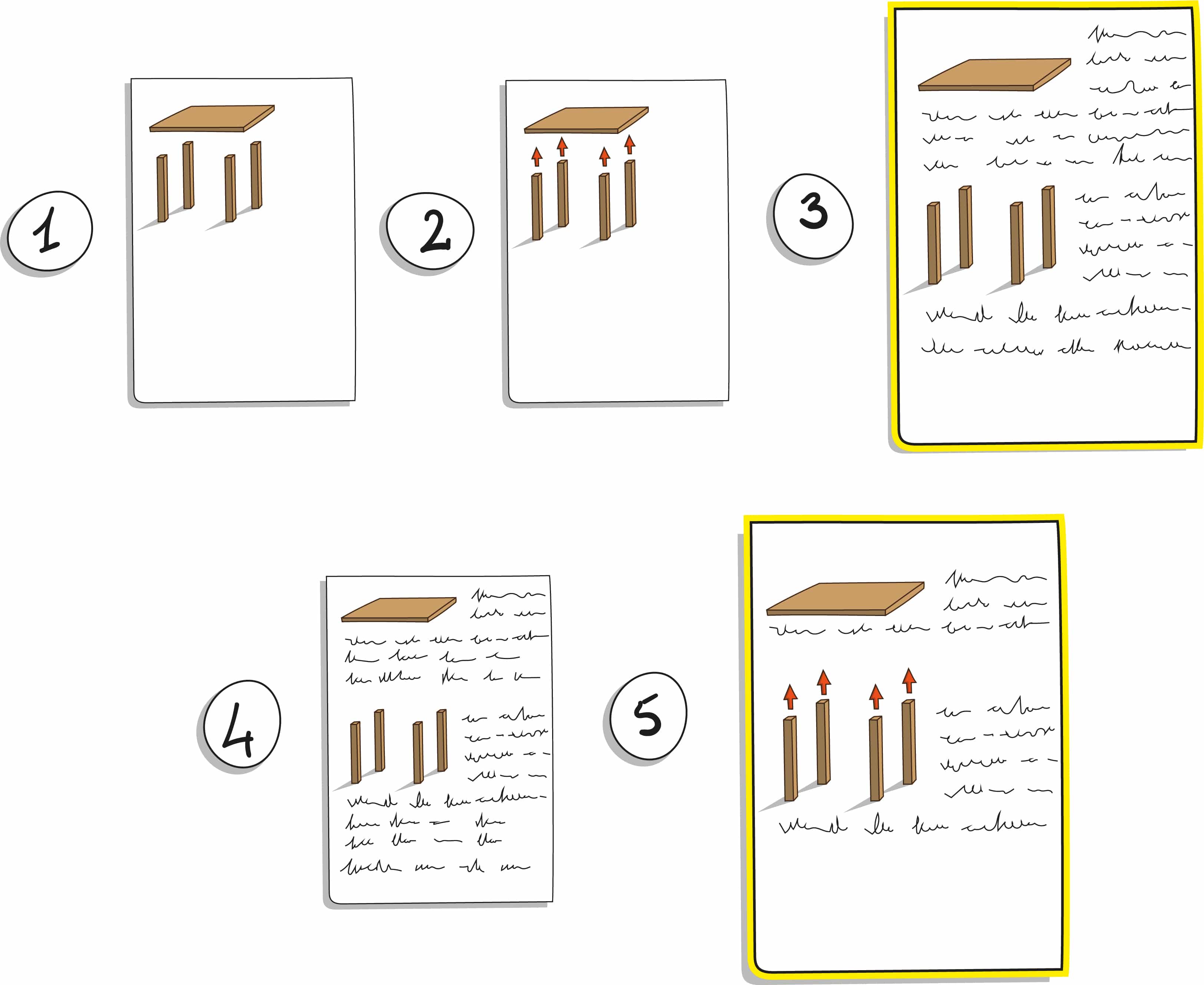

Comparing the effectiveness of animations and static images (Höffler and Leutner)

2. Animations should convey information

The study also showed that the role played by the footage is of great importance in the effectiveness of learning.

If the animation has a didactic function, it performs much better than a static image in most cases. If it is decorative, that is, just a nice addition to the presentation, it performs as well or worse than an image with the same function.

Which form works better depends on various factors, and Höffler and Leutner considered several criteria:

- role of the animation (whether it is supposed to teach something, such as how to create a PowerPoint presentation, or whether it plays a decorative role, so it is just a nice addition);

- type of knowledge conveyed (whether the information can help solve a problem; whether it is declarative, i.e. concerns facts; or whether it describes a process);

- type of material (video or computer animation);

- level of realism;

- text content or lack thereof;

- additional cues in the images (e.g., arrows)

- field of knowledge (e.g., mathematics or biology).[2]

Animations with a decorative function distract the audience with interesting but unimportant details and draw attention away from the actual material, Höffler and colleagues wrote in the 2013 paper “Static and dynamic visual representations.”[3]

If you use it to convey knowledge to the audience, to visualize what you are talking about, then it will significantly increase the value of your presentation.

If you are instructing employees on new health and safety procedures in the company, and in the background you play an animation showing people walking down the street in masks, it may distract them and they will remember little of the training.

On the other hand, if you show employees an animation in which the new company procedures are shown step by step, they are more likely to remember it and implement the steps more effectively.

3. Animations are more effective in explaining procedures

Höffler and Leutner also examined animations in terms of the type of knowledge they convey.

The first type is declarative knowledge – it concerns facts that we can assimilate.

The second is for problem solving.

The third is called procedural/motor knowledge – it helps the viewer understand procedures and processes, or “how” something is done.

When you listen to instructions on how you should properly prepare and print a document, fix a computer, or process an order, you are using this very knowledge. And it turns out that this is where animations can be most helpful.[2]

If the presentation contains a series of static images, we have to combine them in our head into a logical whole. With simple issues we have no problem with it and do it unconsciously.

For example, imagine three pictures.

In the first, a man is standing in front of a printer, in the second he is pressing a button, in the third he is holding a document in his hand and looking at it. We can easily recreate this scene in our imagination. We don’t need animations to know that the man has just printed something and is looking at it.

The challenge begins when we explain more complicated issues.

In 1973, Spangenberg conducted an experiment on this topic. He asked subjects to disassemble a machine gun.

He divided them into two groups: one group was showed a recording, the other group frames from the recording, or static images.

The participants had no experience in disassembling weapons, so they needed clear guidance on how to do it.

The results of the study left no doubt that animations were more effective in this instance. The group that saw the instructions in the form of a video performed much better – the respondents remembered more and were able to apply the knowledge in practice.[4]

Relating this to our presentation on health and safety procedures: if we are explaining to a team how to wash their hands, an illustation will be sufficient. It is not such a complicated procedure that the audience will not connect the illustrations into a logical whole on their own.

However, if you want to take them through a more complicated or multi-step process, such as a new way of using equipment in the plant, you may find that an animation works best. In such multi-layered tutorials, weighing illustration vs animation helps pinpoint the medium that delivers instructions with the greatest precision.

A comparison of the effectiveness of animations and images in following complex instructions,

e.g., instructions for disassembling a machine gun (Spangenberg)

-

Why do companies like Intel, SHARP and Herbalife choose our animation studio?

-

How we can help you reach your goals?

Why is this the case? According to Lewalter, another researcher exploring this question, animation provides the viewer with a ready-made mental representation of movement. It takes over the role of the imagination and relieves the burden on the mind.[5]

In short, if we see something on the screen, we don’t have to imagine it. This doesn’t matter much when printing a file, because we can easily fill in the missing “frames” in our head.

In the case of disassembling a machine gun, showing only images can lead to misinterpretation. That’s why in Spangenberg’s experiment, video proved more effective.

If we want to convey to employees how to use a printer, static images should work.

If we are explaining to employees the stages of implementing changes in the company or to a client about how to use our software, we will get better results using animation than still images.

Misunderstandings will be avoided and the presentation will be more accessible for the recipient.

See how Bank Millennium used animation to educate on procedures and standards: a case study.

4. Illustrations explain simple procedures better

Researchers Michas and Berry were not as optimistic about animation as their predecessors. Many questions were still unanswered. Above all, the researchers wanted to know whether instructions should always go hand-in-hand with animations.Their skepticism reminds us that a thoughtful evaluation of illustration vs animation is essential before pairing visuals with guidance.

In 2000, they investigated this using the example of banding instructions. They conducted two experiments. In the first, they presented the teaching material as:

- text;

- illustration;

- text and illustration;

- video with narration;

- some frames from the video.

The subjects were given the same amount of time, about 4 minutes, to read the content. Participants then completed the same test. The best results were obtained by two groups: the group that was given the text with an illustration and the group that watched the video with a narration.

In the second experiment, the researchers decided to test the effectiveness of messages that suggested movement. This time they showed the subjects:

- simple line illustration;

- the same illustation with arrows suggesting the direction of movement;

- illustation with text describing its content;

- illustation with text describing its content and outlining the steps of banding – so the text filled in the missing “frames”;

- illustation with arrows and text describing the stages of banding.

The best results were obtained by groups 3 and 5, those who received illustations with descriptions or illustations with arrows along with text about the stages of banding.[6]

The researchers proved that animations are not always necessary and are not always the golden means to reach the audience.

If the message is not complicated, sometimes it is enough to choose appropriate images and mark the movement, for example with arrows.

This study confirms previous conclusions. If you want to explain simple procedures to employees or customers, such as how to print files, you don’t need animations for that -as with the instructions for assembling IKEA furniture.

What’s more, it can only introduce unnecessary chaos and reduce the effectiveness of the presentation. Sometimes illustrations are enough.

In studies testing the effectiveness of messages suggesting movement

instructions with illustations and text were the most effective

than instructions with arrows and text (Michas and Berry)

5. Animation versus realistic video

Video and animation are different – one is realistic and the other is not realistic. This became one of the criteria taken into account by Höffler and Leutner during their analysis.

The researchers wanted to see if realism affects how much people remember and how people perceive the material.

Unfortunately, they were not able to come to a clear conclusion.

As already mentioned, animations are much less effective when they play a decorative role. In most of the studies analyzed by Höffler and Leutner, computer animations were just a supplement to the text and did not teach anything.

The opposite was true in studies that used video materials. They conveyed important information and played a didactic role.

The study concluded that it depends on the goal we want to achieve. Realistic recordings can better stimulate the brain to perform certain activities, and therefore can motivate more effectively.

Computer animations, on the other hand, have the advantage of including only the necessary information. They do not distract with excessive details and irrelevant elements.[2]

No one needs to be convinced of the educational role of animation – the previously mentioned Walt Disney is a great example of this. He built an empire, and his cartoons have shaped and continue to shape millions of children. It turns out that they can also teach adults. This timeless influence shows modern brands why they should carefully consider illustration vs animation when designing learning experiences.

In 2018, Robert E. George, an imaginative US judge from the state of Missouri, presided over a case where a hunter had killed about 230 animals, most of them for trophies, in violation of state law.

The judge was moved. He sentenced the poacher to a one-year prison term and to watch the cartoon “Bambi,” the iconic 1942 animation, once a month. The poacher needed to watch the fable about the orphaned deer 12 times.[7]

The judge concluded that Disney fairy tales allow the viewer to absorb important life lessons about relationships with others and about the consequences of our actions.[8]

There is no clear answer as to whether animated or realistic footage is more effective in conveying information. However, there is no doubt that both forms are effective.

Which form you choose to convey your company’s key information is a matter of preference; however, when weighing illustration vs animation, it is critical to align your choice with the goals the video is intended to fulfill.

If you want to find out what form of video to choose, read our text: Product videos—types, prices, advantages and disadvantages (classic film, whiteboard animation, vector animation, and 3D animation)

A person that killed about 230 animals was given an unusual punishment in 2018:

While in prison for one year, he was required to watch the animated film “Bambi” once a month.

-

Why do companies like Intel, SHARP and Herbalife choose our animation studio?

-

How we can help you reach your goals?

Explain Visually – Your partner in visual communication

Over 8 years of experience

More than 500 completed projects

19 languages

Over 100 companies

Explain Visually is not just an animation studio. If you are open to working with us, we can become your strategic partner in creating effective visual communication that delivers measurable results.

Our experience covers the full spectrum of services, from digital illustrations and infographics to animated films and explainer videos. We combine expertise in creative processes with technological advancement, using both traditional techniques and the latest digital tools. With this versatility, we guide clients to the right choice in every illustration vs animation decision.

We guarantee commitment to understanding your needs and desired outcomes for your project. Within our team, we have developed a proven system of cooperation, which includes needs analysis, consultation workshops, and refining messages. Our award-winning team is recognised for its innovation and quality, consistently ranking among the top animation studios.

See our portfolio on YouTube.

Summary

Illustration vs animation? What should your choice be? There is no ready-made answer here!

The choice between illustration vs animation should be driven by the complexity of the message, the target audience, and the desired career outcomes for your project.

For straightforward instructions or when you need to create detailed artwork that stands on its own, illustration is often sufficient. However, when you need to convey complex ideas, explain multi-step procedures, or engage viewers on various digital platforms, animation is the superior choice.

Animation may be the missing link in your presentations.

As Höffler and Leutner showed in a meta-analysis of 26 studies, animation should convey some knowledge.

If it is “about nothing”, i.e. it is only a nice background for the speech, it may distract listeners but it is perfect for explaining complicated processes and procedures. It leaves no room for imagination mistakes, as it shows the audience HOW something is being done, step-by-step.

The phrase “complicated processes” is crucial here. As Michas and Berry have shown, in the case of simple instructions, the use of text and a well-chosen image is perfectly adequate. So to reiterate Walt Disney, “animation is the most comprehensive and direct form of communication”.

And communication in business is the key to success. Do you want to show customers how to use your services? Do you want to show your employees how to implement new procedures? Show them as sometimes words aren’t enough. Because in the realm of effective corporate messaging, the smart evaluation of illustration vs animation can turn complex ideas into clear action.

Bibliography:

[1] Randi J. Rost, OpenGL Shading Language, 2006

[2] Höffler, Leutner, Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis w: Learning and Instruction 17, 2007

[3] Höffler, Schmeck, Opfermann, Static and dynamic visual representations: Individual differences in processing w: Learning through visual displays, 2013

[4] Spangenberg, The motion variable in procedural learning w: Communication Review,1973

[5] D.R. Fraser Taylor, Tracey Lauriault, Cybercartography: Theory and Practice, 2005

[6] D.C. Berry, I.C. Michas, Learning a Procedural Task: Effectiveness of Multimedia Presentations w: Applied Cognitive Psychology, 2000

[7] Missouri poacher ordered to repeatedly watch Disney movie ‘Bambi’: https://eu.elpasotimes.com/story/news/2018/12/17/missouri-poacher-ordered-judge-watch-disneys-bambi-repeatedly/2339713002/

[8] Watch ‘Bambi’ Monthly in Jail, Judge Orders Man in Deer Poaching Case: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/18/us/deer-hunting-bambi-sentence.html